This month I wish to present a group that I have been working on for nearly 30 years, the angiosperm genus Viola which comprises violets and pansies (Figure 1). Our group recently produced a monograph of the genus (Marcussen et al. 2022) – the first comprehensive (and very much needed) revision of the genus since 1925!

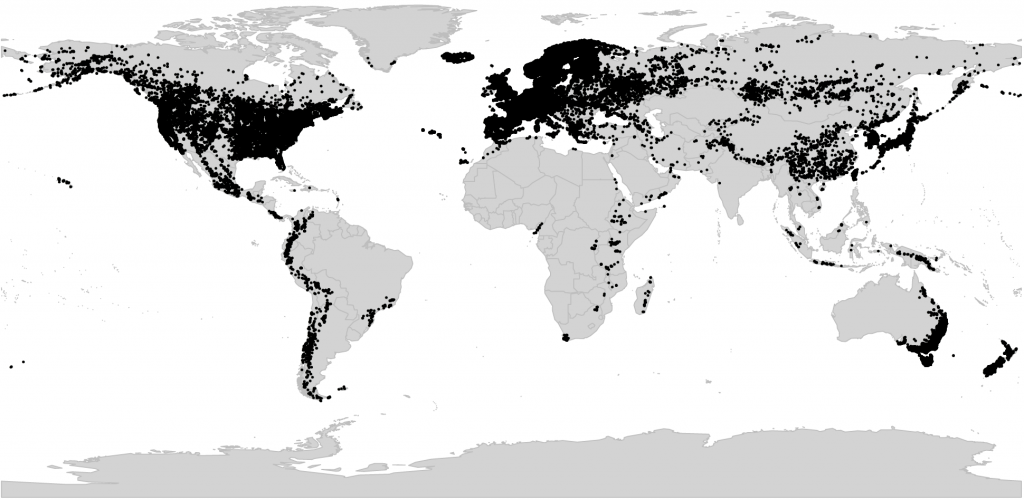

Viola is nearly cosmopolitan and with c. 675 species currently known, it is among the 40 largest among angiosperms, the fourth largest within order Malpighiales, and the largest within the Violaceae family (1200 species). It is the only temperate genus in the otherwise tropical Violaceae (Figure 2). Eighteen species occur in Norway.

Violets and pansies are familiar plants and have a long history in European folklore, with the first records from Ancient Greece. Owing to their fragrant flowers, Viola odorata (Sweet Violet) and filled forms of V. alba (Parma Violets) have a long history of cultivation for the perfume industry and as ornamentals and other species have also been used for food or medicine. Viola is rich in cyclotides, a family of cyclic, chemically stable plant peptides, and much research is currently aimed at using these as scaffolds in drug design. Viola is one of a very few angiosperm lineages that has evolved seasonal cleistogamy: in spring the plants produce showy insect-pollinated flowers, and in summer closed and petal-less, self-pollinating flowers as a reproductive back-up. The seeds of Viola have fatty appendages (elaiosomes) and are usually dispersed by ants, a feature shared with numerous spring-flowering taxa.

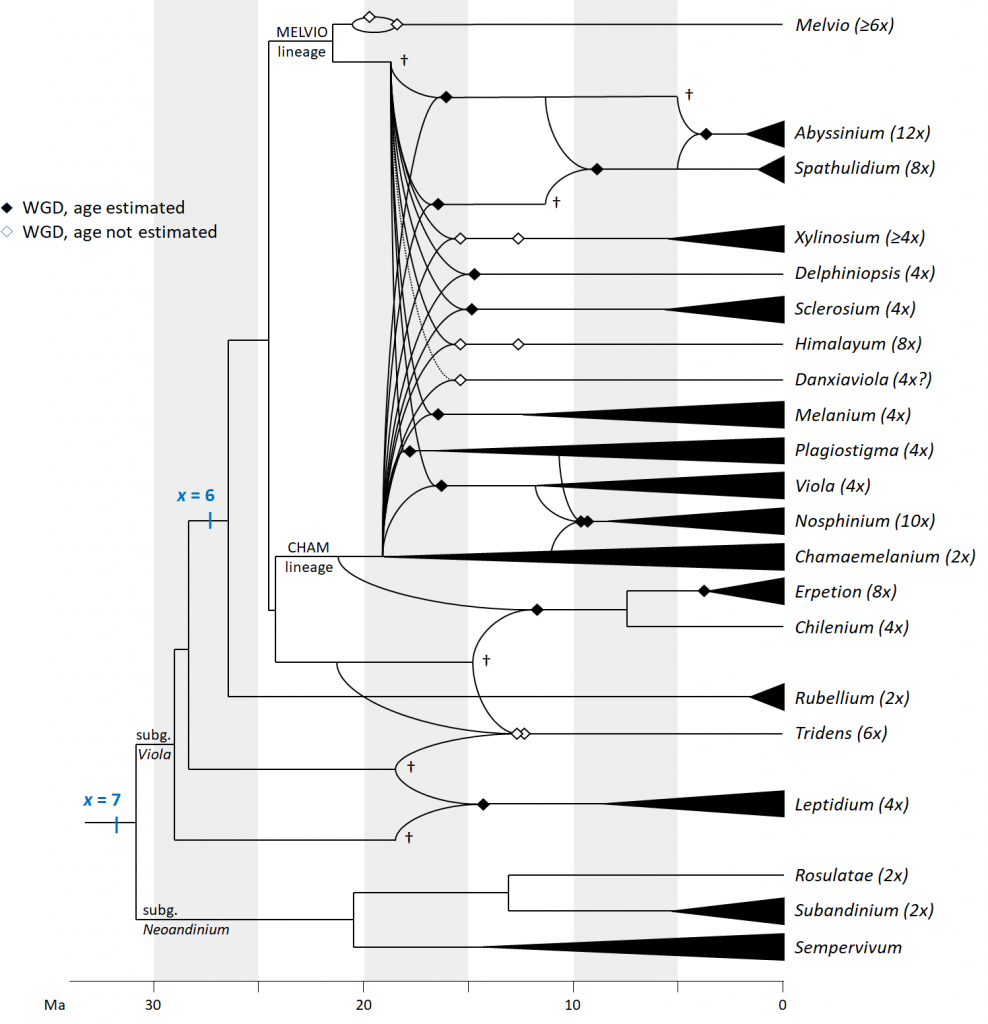

The overarching evolutionary history of Viola is fairly well understood (Figure 3). Quite unusual among widespread temperate lineages, Viola originated in South America, probably in connection with the Andean orogeny. It began diversifying during the global cooling event ca 34 million years (Ma) ago, in early Oligocene. Around 20 Ma ago, two sublineages made it into the northern hemisphere, and have since diversified into more than 500 species. This marks also the appearance of Viola seeds in the fossil record. One of the peculiarities of Viola is the extremely high frequency of allopolyploid formation throughout its evolutionary history. Most of its sublineages (treated taxonomically as sections) originated by independent polyploidisation several Ma ago, in many cases in connection with long-distance dispersal and colonisation of new areas. Ploidy levels as high as 20 or 24 have been documented within sect. Melanium in Europe. It is believed that the main driver of allopolyploid formation in Viola is the combination of a lack of barriers to hybridisation, which may persist for 18 Ma or more after lineages diverged, and the ability to reproduce by cleistogamous self-fertilisation.

Most recently, our group has documented a complex interplay of postglacial recolonisation and introgression involving the temperate Viola epipsila and arctic V. suecica (sect. Plagiostigma) in northernmost Fennoscandia (Sollien 2024) (Figure 4). Our preliminary results indicate the transfer of adaptations to the high-latitude climate and light-regime from V. suecica into V. epipsila in this northern region.

Featured image are: Viola tricolor (big flowers) and V. arvensis (small flowers). Photo: Thomas Marcussen

Literature:

Marcussen, T., H. E. Ballard, J. Danihelka, A. R. Flores, M. V. Nicola and J. M. Watson, 2022. A revised phylogenetic classification for Viola (Violaceae). Plants 11(17): 2224. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11172224

Sollien, M. B., 2024. Hybridization and introgression in the European marsh violets. M.Sc. Master thesis, University of Oslo. https://www.duo.uio.no/handle/10852/112332?show=full

![]()