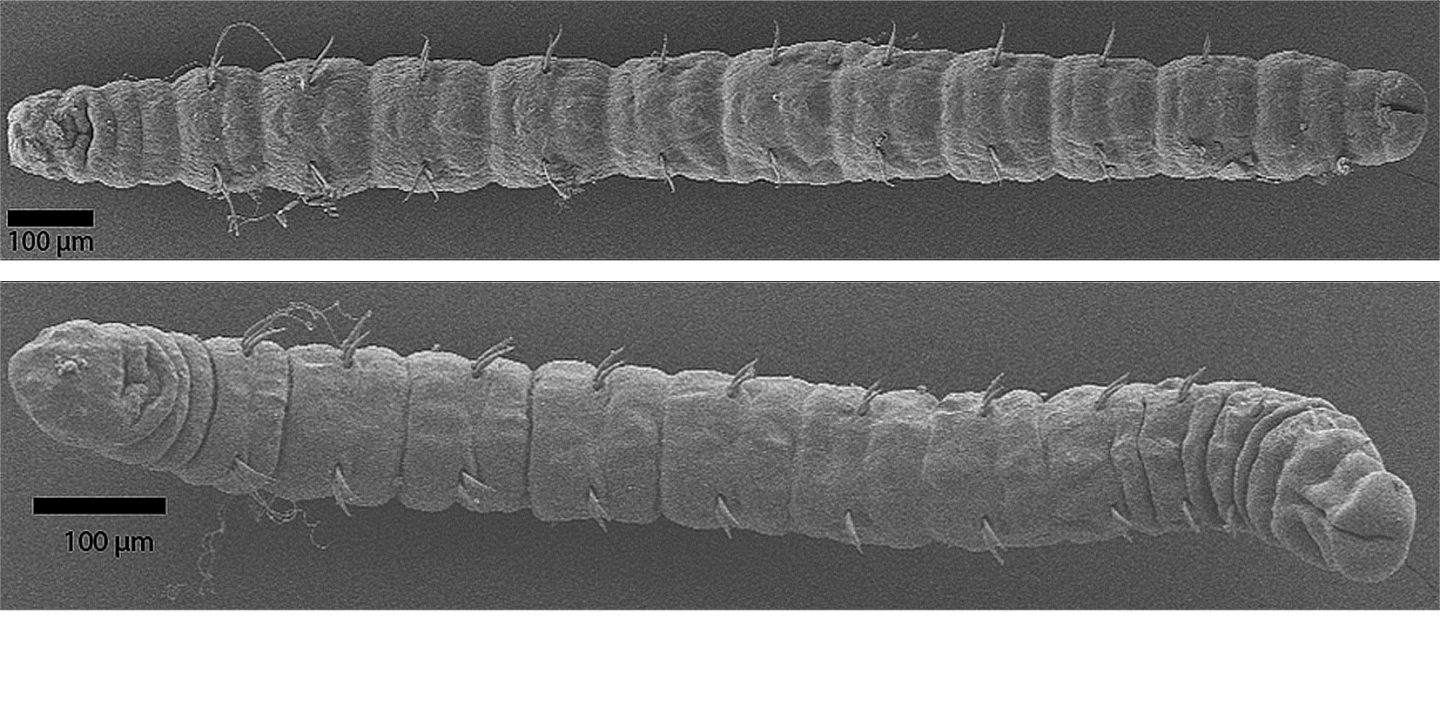

Species of the genus Stygocapitella belong to the ringed worms, also known as Annelida. Annelids are worms like earthworms, lugworm or christmas tree worms, but also leeches or very tiny worms living in the spaces between the sand grains, called the interstitium. Such an interstitial group of worms is also the genus Stygocapitella. They occur at sandy beaches all around the world in temperate and arctic climates, even here in Norway all the way up til Tromsø. One can find the small worms of less than 3 mm body length around or above the high water line in a depth of 10 to 60 cm. So essentially, often beneath your beach towel.

We, and especially our former PhD student Jose Cerca, did a lot of research on these species and we found a lot of interesting and fascinating things about them. The latest results on these worms were published this year, but hopefully more will come in the future.

What makes them so fascinating and interesting?

Originally, only one species has been described occurring all over the world, but our research showed that there are more than 10 species and the number is still growing. Hence, their distribution is much more restricted. They are also a classical example of cryptic species with this as despite the more 10 species we can recognize using molecular data, morphological only four morphotypes can be found. Hence, several species are identical even taken different measurements like body length into account.

On the other hand, even though the distribution is restricted within each new species, the genus is globally distributed, you can it them in both Northern and Southern hemisphere, in the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Ocean. Also many of the species are distributed over large regions like the Northern part of the US East coast or the Northern coasts of Europe. This wide distribution occurs despite these species having no known distribution stage. They have direct fertilization. The eggs are deposited in a sac attached to a sand grain. The development is direct and no pelagic stage is present. The adults are bad swimmers as well. Nonetheless, our results showed that they have crossed the Pacific in East-West direction (or vice versa) at least two times and that gene flow is going on over substantial distances. With this they are also a classical example of the Meiofauna complex. How they disperse is still unknown?

Another aspect in that they show what is called a bipolar or better anti-tropical distribution. They have not been found in beaches of the tropics or subtropics so far, despite a few attempts. They seem not to sustain in such habitats. Nonetheless the genus can be found on both hemispheres. Moreover, our results indicate that Stygocapitella must crossed the equator at least twice. How did they accomplish this if they are bad dispersers and there seem to be no suitable habitats for “resting” on the way?

The last and most fascinating things is: Some of the species are incredibly old?

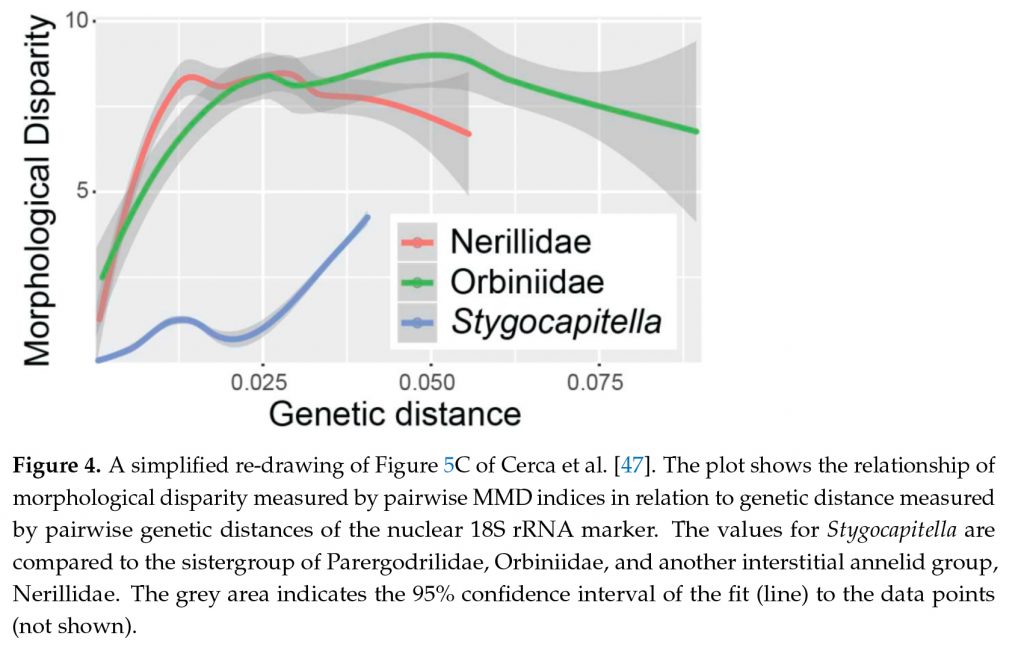

As mentioned already, many of the species are morphological identical. This means one cannot by visual clues decide which species one has. This is something with happens actually quite often in many invertebrate species, that we are dealing with such cryptic species. However, our results showed that some of the Stygocapitella species are also exceptional in this way. Their morphology has not changed for more than 100 million years. So when this body plan evolved, the dinosaurs still walked the Earth. It was such a successful design, that it remained this way ever since. This is an truly incredible case of the so-called morphological stasis as it is known mostly from paleontology. To our knowledge, it is the longest known period of an completely unchanged appearance of one or several species. This makes Stygocapitella an ideal system to study stasis and what cases this evolutionary phenomenon. So far, we could only show that it is not ongoing gene flow causing an identical morphology. On the other hand, also at the genomic level a huge degree of variation seem to be shared across different species.

![]()