For April’s group of the month, we’re tackling a whole phylum!

As phyla go, Loricifera are one of the newer kids on the block, having been first discovered in only 1983. Since then, 44 species have been named, ranging from France to Antarctica to Japan, and more are being discovered every year. I wrote an article about new loriciferan discoveries during our advent calendar last December – because they are so new, there are always exciting new things to say about them!

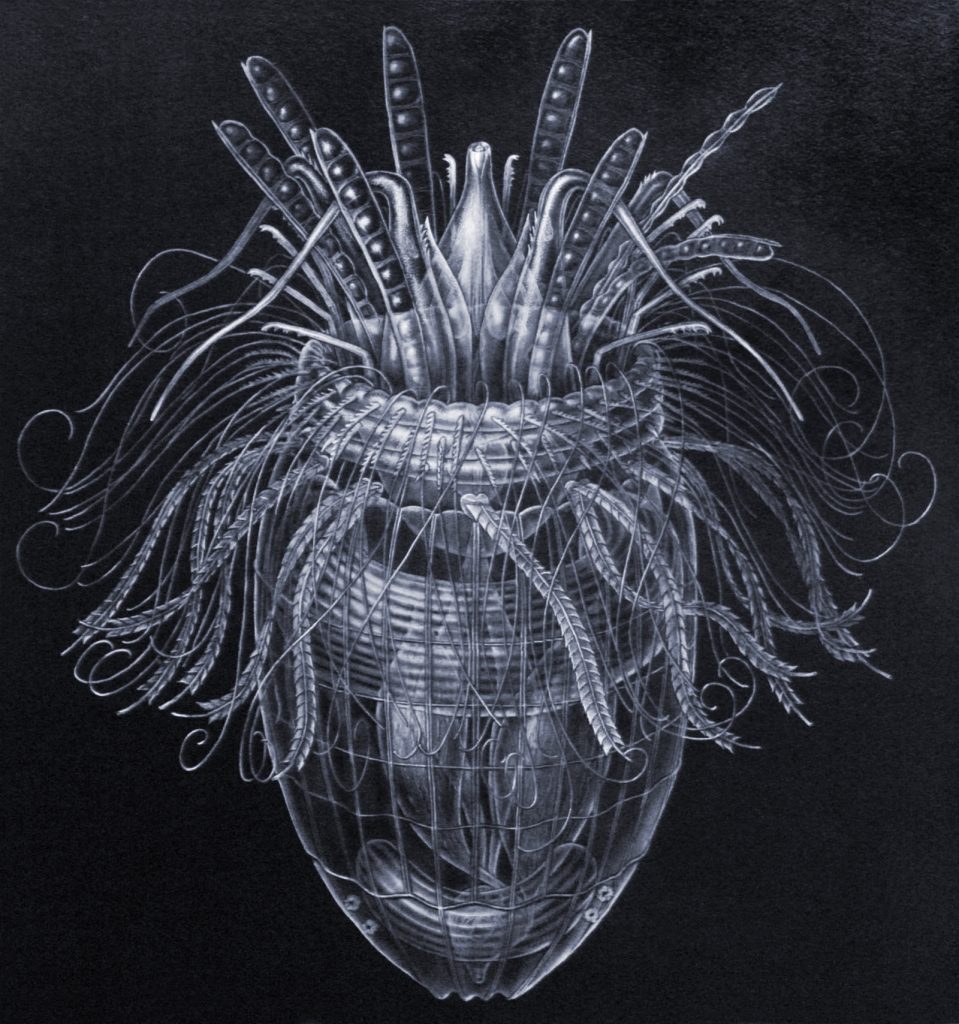

Loricifera belong to the Ecdysozoa, the group of animals that also includes arthropods (insects, crustaceans and their close relatives, like centipedes, millipedes and spiders) and tardigrades. With their especially close relatives in Kinorhyncha and Priapulida, they also make up this interesting superphylum called the Scalidophora – a group comprised entirely of small ocean-dwelling animals. They all share scalids –small spines that come in a wide variety of different appearances across species. These are used both for locomotion and for sensing the environment around them. I personally think the Loricifera are one of the most astoundingly beautiful animals on earth, and the combination of their tiny size with the delicate intricacy of those scalids never ceases to amaze me.

So why did it take us so long to find such a widespread group? What makes them so unique? And why were they so elusive?

The largest Loricifera is about 1mm long, and they all live in sediment at the bottom of the sea. Some species of Loricifera live in relatively shallow sediment – at around 150m below the sea – but others live so far down that we have only recently even been able to look at the environments in which they live, let alone find them! Fafnirloricus polymetallicus, for example, lives 5km below the ocean’s surface, in the deep abyss. In addition, some species have been found in sediments in the deep sea that contain no oxygen – in these conditions, they have abandoned traditional respiration (and even mitochondria) to instead generate energy by metabolizing a chemical called pyruvate, which is one of the waste products of respiration in animals like us. These kind of adaptations to a totally oxygen-lacking habitat aren’t found in any other animals, which makes them quite unique as extremophiles.

So they’re tiny, and some of them live in the deep deep sea, but that can’t be the only reason, right? Their cousins the kinorhynchs also live 150m down, but they were first discovered in the 1880s. What made – and makes – Loricifera so uniquely hard to find?

The secret is rather sticky. Quite literally.

Loricifera attach themselves firmly to the sediment they live in using adhesive glands. They grip so firmly to this sediment, in fact, that to collect them they need to be startled off their perch by spraying freshwater over them! This tight bind combined with their small size means that even an experienced microscope user might mistake them for a grain of sand and pass over them. This incredible adaptation keeps them safe from ocean currents – but it serves as a very effective kind of camouflage by extension!

As we explore more environments, particularly seamounts and the deep sea, with new eyes, we find that the vast diversity of animal life exists in places and forms that we might not have otherwise ever considered. The Loricifera are a brilliant reminder of that – that there are still new frontiers of our own earth we have yet to explore, and new wonders to find.

And sometimes, really, that it all just depends on looking at things with a new perspective.

![]()