In the last month, Sunniva Løviknes and Jan Einar Amundsen successfully defended their Master theses they had conducted the last two years in our group. Congratulations to this very interesting project. Both worked on very similar topics. Around the world the number of artificial beaches and even islands are increasing. The most prominent examples are probably Palm and World islands of Dubai. However, also Oslo has gotten its share of artificial beaches for recreational purposes like Sørenga and Operstranda. As these beaches are usually placed at sites where there were no beaches before the question arises are they able to sustain a habitat for the small organisms (called meiofauna), which are usually found at these beaches. If they can sustain this biodiversity, the questions arises where do the species come from.

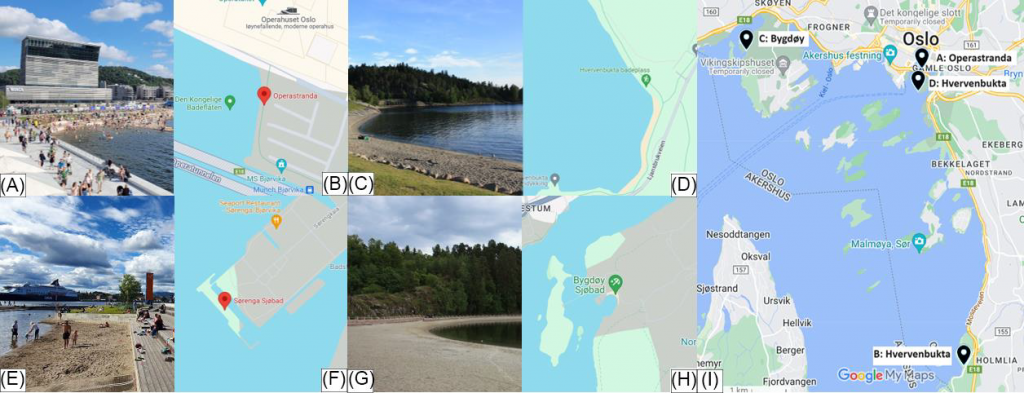

These questions were addressed by them using different methods; each concentrating on different animal groups occurring in this special habitat. They took samples from the two artificial beaches Sørenga and Operastrande and the two natural beaches Hvervenbukta and Bygdøy. Unfortunately, the two natural beaches were not totally natural as there at been beach replenishment and hence substantial human impact. Nonetheless, they occur at sites were beaches form naturally and hence should be able to sustain a meiofaunal community.

Sunniva and Jan used two approaches to address their research questions. First, they used the traditional way by counting the numbers of specimens of their groups they found in each sample and sequenced two molecular markers to assess where they came from. Second, they used a very modern environmental DNA (eDNA) approach. This means all DNA occurring in the sediment sample is extracted and then in their case the same two molecular markers were used to assess, which species occur in the beach. This approach allows to detect any specimen that left behind some DNA at the beach and not only the ones that live there, but of the latter there is much more. However, due to this they could not only detect species from their groups of interests, but also dog, chicken, pig, and hummingbird. Chicken and pig are probably from remains of beach BBQs but how a hummingbird came to beach in Oslo is beyond our comprehension.

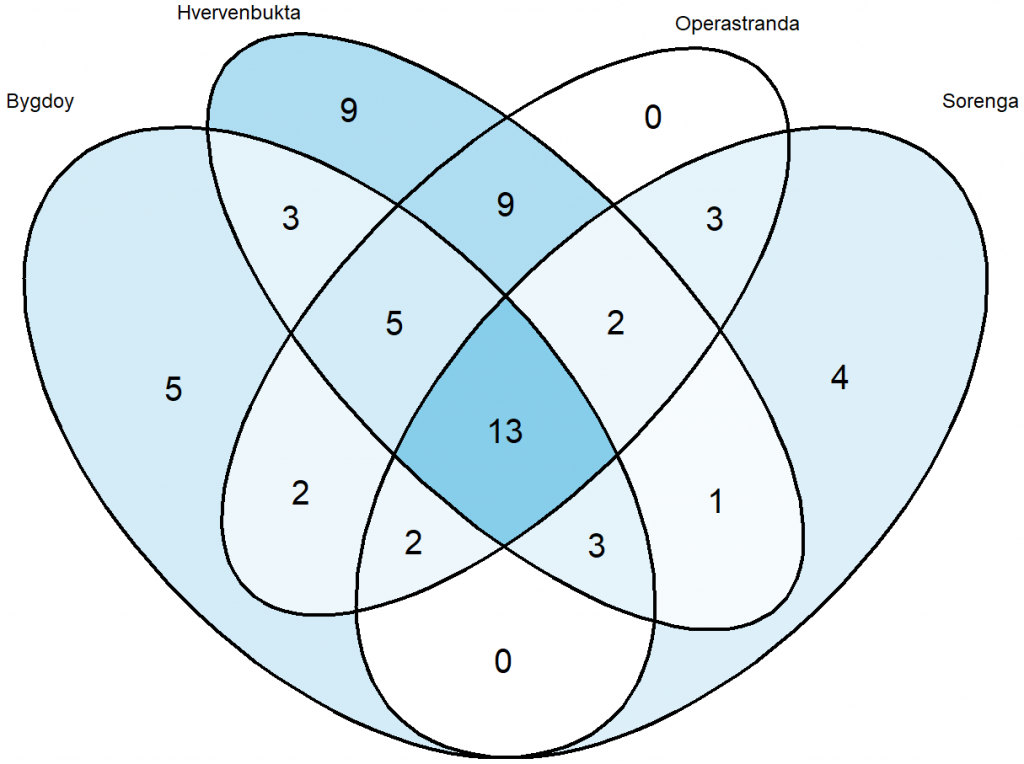

In any case, concentrating on their groups they found that one could find a few species at the artificial beaches, usually in low numbers of specimens. The eDNA approach revealed then that there even more species in these beaches than detected by the traditional approach. Nonetheless, in general the natural beaches, especially Hvervenbukta, had usually more species and more specimens than the artificial. However, further analyses showed that the most decisive factor in the differences between the four beaches was not so much if they were natural and artificial but if they were more or less exposed to wave action. Finally, the molecular data also revealed a strong overlap between the species occurring at natural and artificial beaches. Hence, the most likely explanation is that the species colonized the artificial beaches from beaches close by and not from distant beaches.

![]()