The Biodiversity Genomic Europe (BGE) project has three streams dealing with the biodiversity crisis. In the blog so far, we have mostly presented about one stream, the European Reference Genome Atlas (ERGA) one concentrating on the genomic side of the project. However, another stream is concentrating on the Barcoding community (BioScan) and its approach to monitor biodiversity. The third stream brings these two streams together in a complementing manner. Our group is also involved in the BioScan stream. As group at the museum, we contribute to the task 4.3 “Museum sampling”, which fills gaps in barcodes for the tree of life from the material in our collections. As most of the material is old and often not preserved in a manner allowing easy determination of barcodes, the barcodes are determined using a genome skimming approach. This means instead of determining the barcoding gene specifically the genome is sequenced randomly and the barcode pulled from these random sequences.

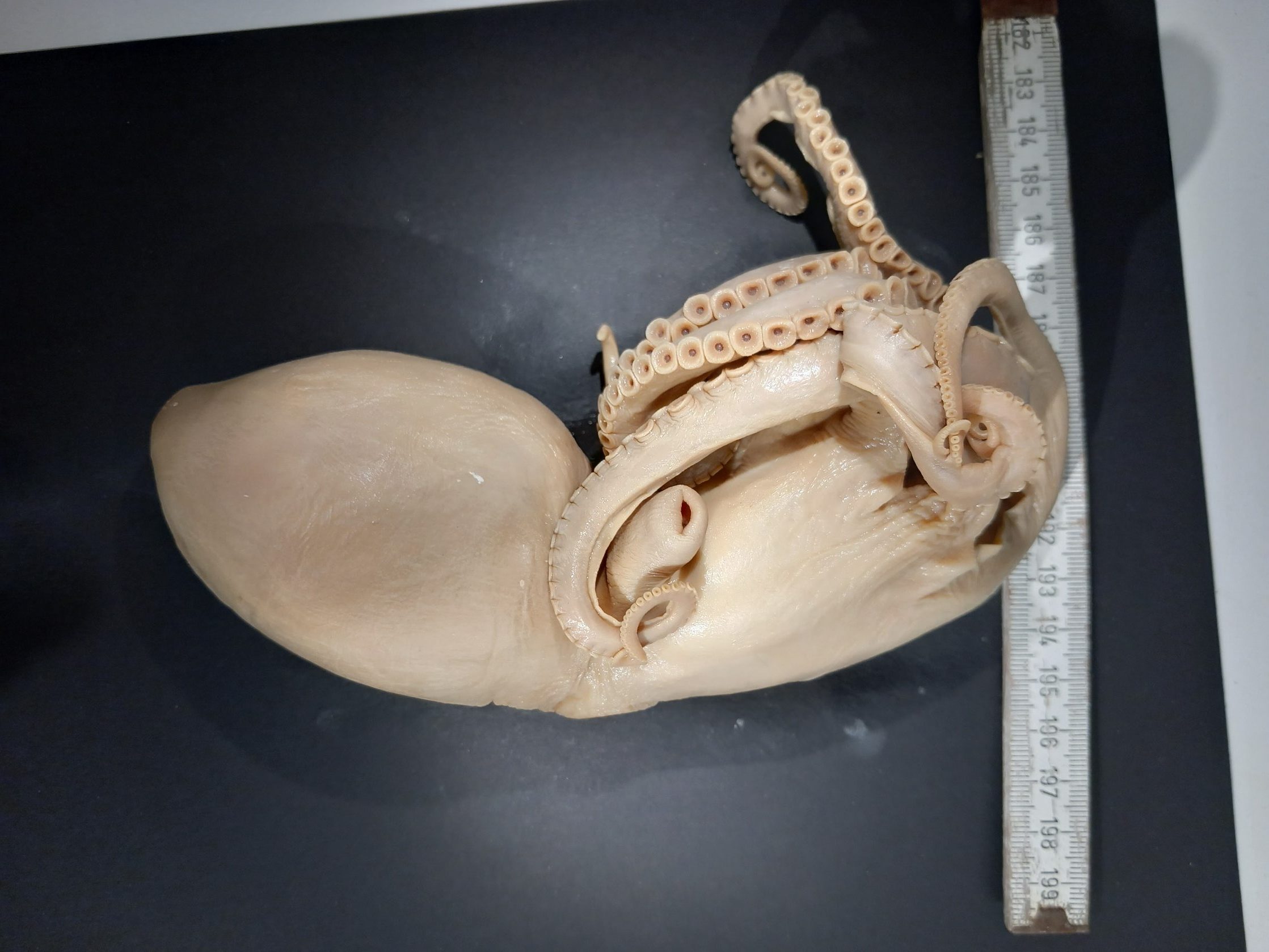

To contribute to this endeavor, we are not only working with collections in our responsibility, but we invited everybody from the museum to contribute with specimens. As a first step, one of our cooperation partners, the Bavarian Zoological State Collection, has generated a gap list for all animal species. This we shared with the curators of the Zoological Collections so that they could check, which species they could contribute from their collections to fill in the gaps. This summer we begun with picking small tissue samples (e.g., a leg of an insect or a piece of the foot of a snail) and transferring them to a plate with 96 samples for shipment to the sequencing center. This sounds simple, but it is quite a laborious task and takes about two to three weeks total from locating the specimens in the collection to the shipment.

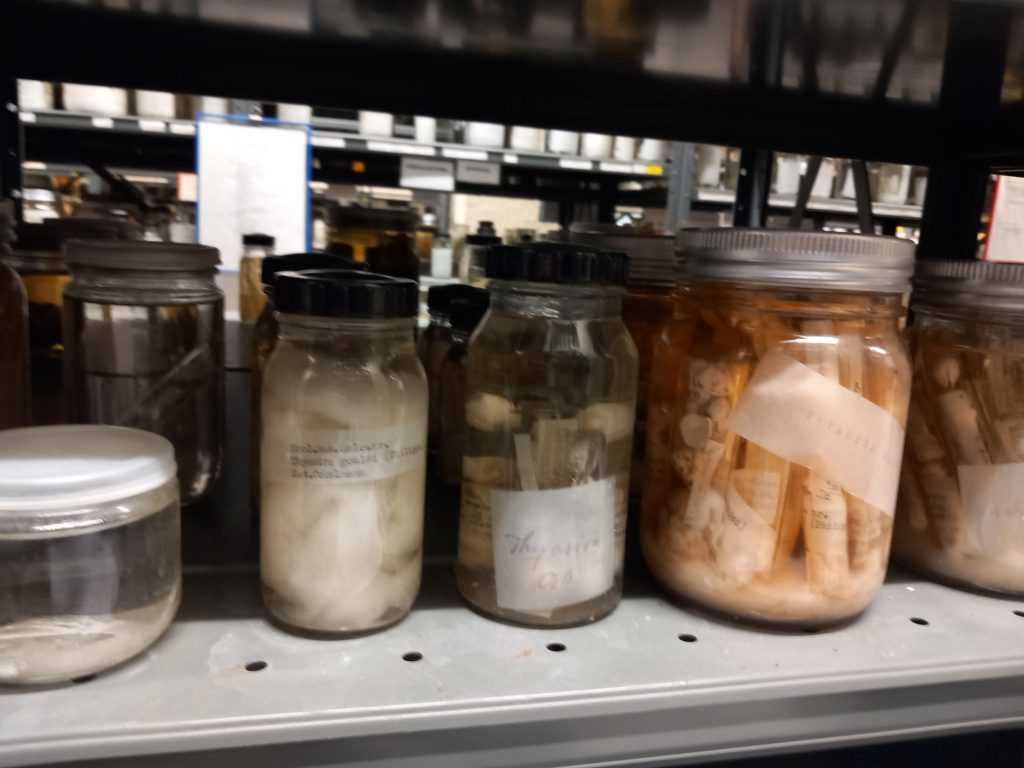

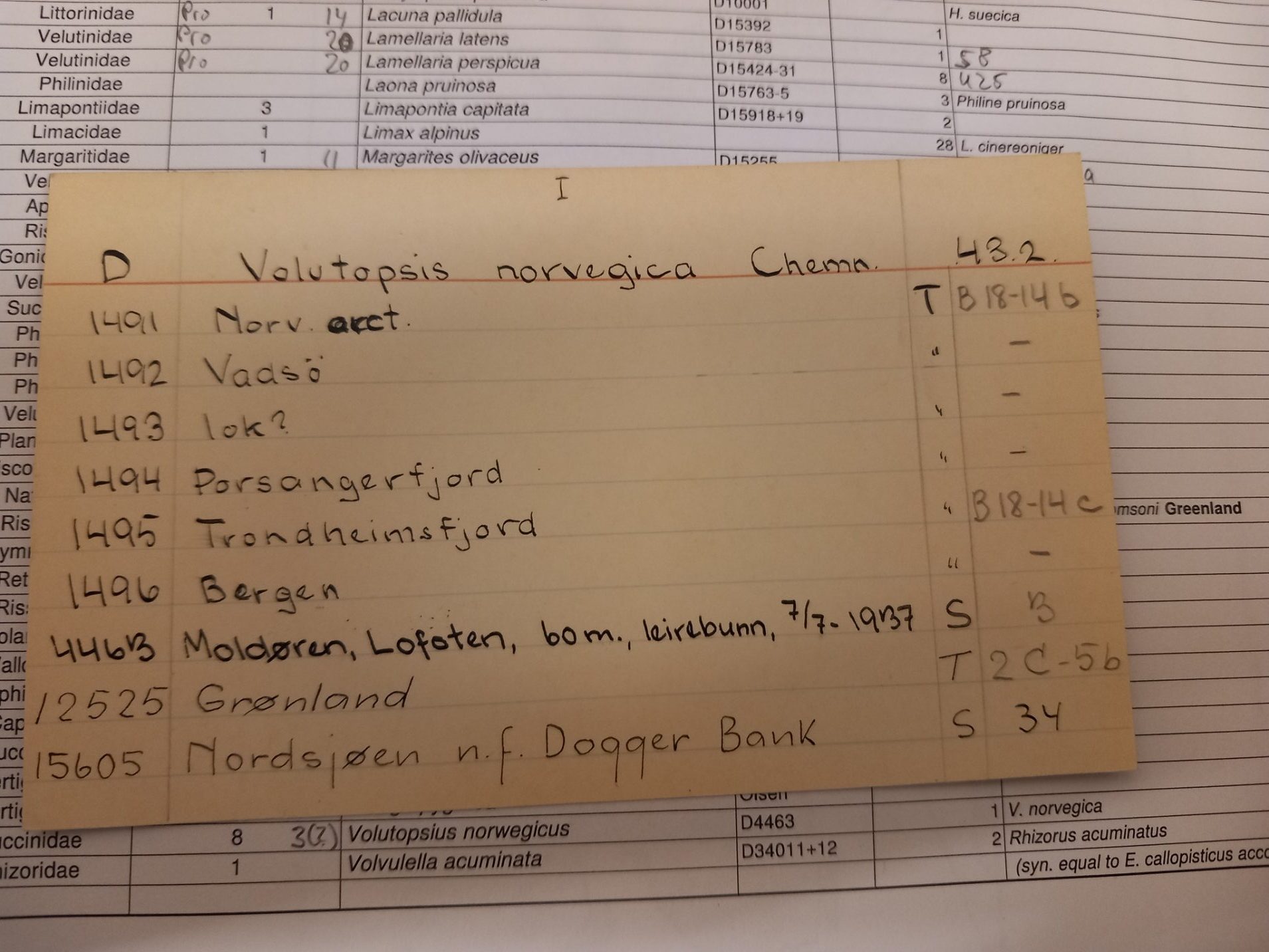

The first step is to locate the sample in the collection. As we already know, which species we want, we can check our catalogues to see where it is. For many collections this means we can check an digital database in our museum to see where they are. Then we can go an get it from that place. This was, for example, the case for the insect families of Diptera and Hemiptera we started with. However, for some collections, we do online have the records in the old fashioned way as an entry in a journal book for the collection. This is for example the case for the mollusk collection, we worked on this month. However, finding the specimen in the journal book is only the first step. Then we need to check the cabinet with the species cards to find the number of the jar that contains the specimens. Then we have to find this jar in the collection. These jars are then brought to the lab for further processing. An additional challenges is that due to fire-safety regulations we only have access to the wet collections until 10 am. Hence, we have a small time window to find them.

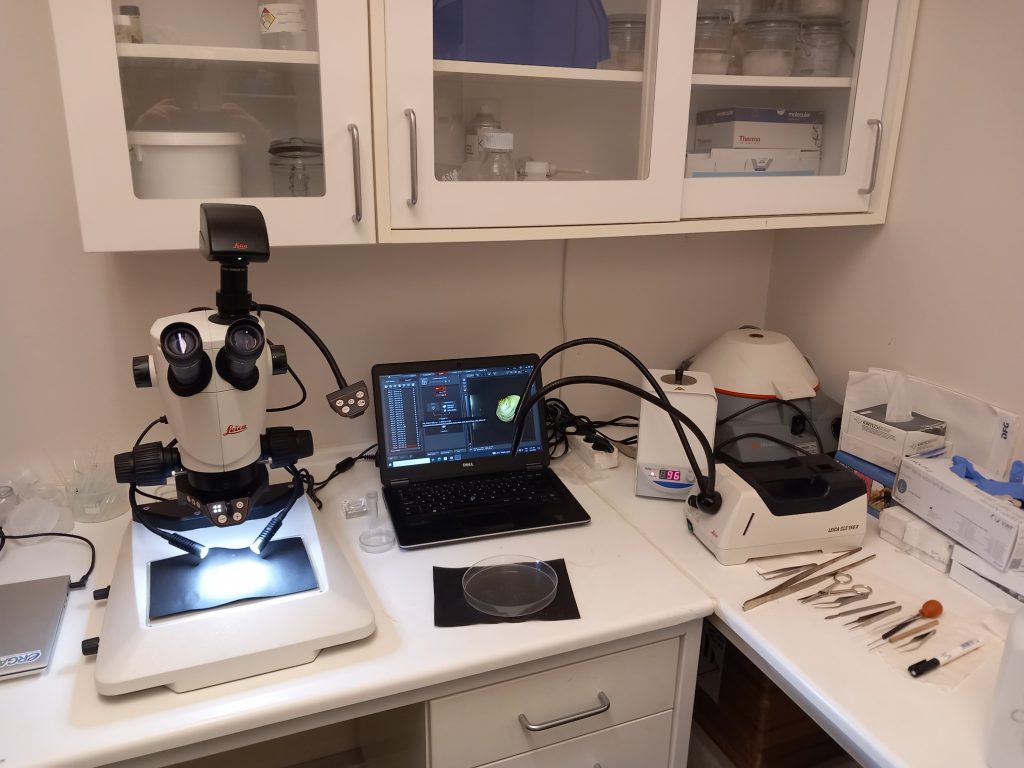

In the lab, we then take pictures of the specimen either directly or using the stereo microscope. After this we take a small piece of tissue, for example, by cutting it out and transfering it to the well with 100% ethanol in the well for preservation until it get sequenced. As we do not want to contaminate the next sample with DNA from the specimen before. All tools used are sterilized by heating them at 280 C for 5 minutes. In the meantime and later, all the information for the specimen is entered into an excel sheet, which is shared with sequencing center as well as uploaded to BOLD (http://www.boldsystems.org/). Before the sending the plate with tissue samples to the sequencing center, a Material Transfer Agreement (MTA) is signed by the museum as well as the sequencing center regulating what will happen with the sample, who is the owner of it and what happens with left-overs. When all of this is in place, it can be finally shipped off. Hence, what sounds like a simple “We take samples from our museum specimens and send them to the sequencing center” is actually quite an effort and takes time.

Maybe some of you followed the discussion about the insect collection at NHM and moving parts of it back to NBIO (see for example this latest Khrono article in Norwegian). As a background, about 18 years ago NHM was approached to store and make accessible the insect collection of Skogforsk and Plantforsk, which is now NBIO. In this agreement (also a form of MTA), the ownership remained with now NBIO, but NHM was to store and manage the insects forever. However, 8 years ago NBIO wanted them back and this year a political decision at the absolute departmental top level granted this request. This is a huge burden for the museum. If we take the effort for this approach as an example, it takes about 100 hours for about 100 specimens. This means it is one hour per specimen. In this case, we are speaking about 100,000 specimens and accordingly 100,000 hours or 4,166 days or 595 weeks or 11.4 years. The procedure in the two cases are slightly different, but there are also many tasks associated with this process. This includes finding the specimens, properly decommission them for the collections and packing them for transport so that they do not get damaged. Even if we calculate only with 10 minutes per specimen for this, we are still at about 2 years of working time.

![]()