They may look a bit like bacteria, but Placozoans are actually animals! These microscopic blobs might, in fact, be key to understanding our own deep evolutionary history, and how the diversity of other animals came to be. Although they were discovered way back in 1883, there are only four named species of Placozoa – one named as recently as last year (though the researchers in this group claim to have identified more on the way, so watch this space!). These four placozoan species are also each considered so different that they are also all their own genera: Trichoplax adherens, Hoilungia hongkongensis, Polyplactoma mediterranea and Cladtertia collaboinventa. That makes them about as different from one another as a dog from a fox.

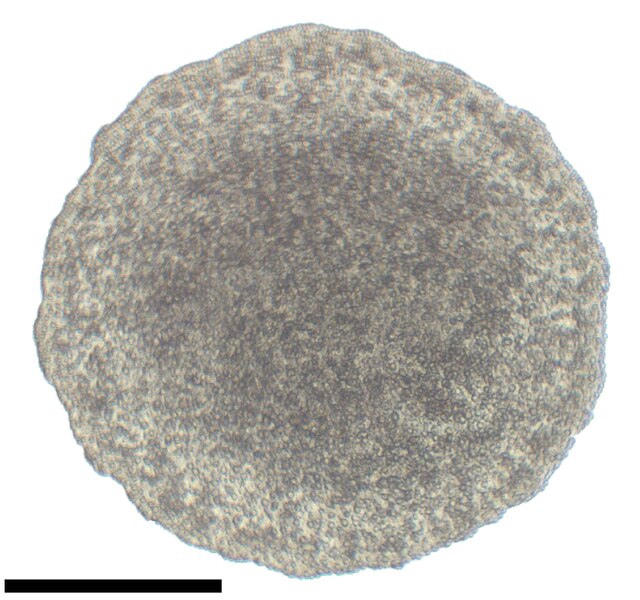

Placozoa tend to be about 0.5 mm to 3mm in size and can be found across the world. Appropriately for July’s group of the month, they tend to prefer it where it is warm: you might find Polyplactoma relaxing in the Med, or Hoilungia hanging out in the beautiful mangrove swamps of Hong Kong. As you might expect with that description, they like salty and brackish water in the tidal zone – they can move around freely, and we tend to find them stuck to roots, shells or rocks, where they feed on algae.

What makes Placozoa so fascinating, though, is that they are about as simple as you can make a thing and still sensibly call it an animal. It has some traits that we might recognise – they have cells with mitochondria, and they have layers of epithelium, which means they have tissue: muscle and ‘skin’. But at the same time, they have no mouth, no gut and no nerves. They feed by totally engulfing the algae, then digest externally against the rock. It could be that this way of feeding is the ancestral way of doing things – a gut, after all, is really just us making a hole inside ourselves so that we don’t need to push up against rocks anymore.

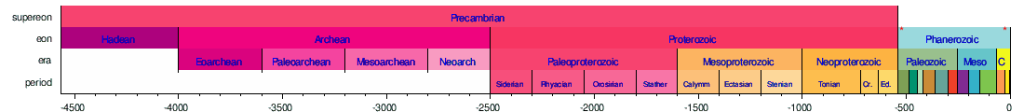

Whenever we try and reconstruct the evolution of animals, Placozoa always appear as one of the earliest diverging groups – this means that we shared an ancestor with them somewhere around 800 million years ago, in a period of time called the Tonian. It’s worth noting, though, that this doesn’t mean our ancestors from that long ago looked like placozoans – they’ve had over 800 million years on their own to adapt and specialise to their own exciting, peculiar lifestyle. What it does mean is that our shared ancestor had traits that likely resembled both of us – though maybe our greatx800 million years grandparents might have some opinions about our decision to move onto land and never visit. One of the biggest debates in phylogenetics right now is about which animal group turned up first: some evidence suggests that it was the comb jellyfish (the Ctenophora/Ribbemaneter). Other evidence suggests it was the sponges (the Porifera/Svamper). Understanding more about the Placozoa could be a way to resolve this debate – if they are the earliest group to arrive, then that extra data might help stabilise the rest of the phylogeny and stop it from moving around, giving us a clearer answer. Even if not, they might still clarify our understanding of how some of our most ancient ancestors might have looked. Better yet, they might make the whole argument even more confusing, which is often the way with biology.

Overall, Placozoa are small but mighty – they’re important to understanding why animals fit together and work the way that they do but they’re also a joy to watch in their own right, as they go about their daily business. If you’re sunning yourself on the beach this month, spare a thought for the humble Placozoa that might be rummaging around through the algae nearby.

![]()