For the 16th day of our Advent Calendar, I’d like to talk about a pre-print. I thought the results were incredibly exciting and, if the article passes peer review, I assume we’ll see it in a journal in the new year!

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.07.25.501387v2.full

The transition from sea to land is one of the most dramatic and beguiling changes in the evolution of life. It has happened multiple times across the diversity of animals, and moving between the two environments comes with a great deal of new challenges. One of the most important is, well, not drying out! That means keeping the parts that need to be wet wet, and balancing the amount of salt on the inside against the amount of salt outside. This process is called osmoregulation. It is substantially easier, as you might expect, in saltwater: although most fish have a range of salinity tolerances that affects where in the ocean they can live. For mammals like ourselves, it means drinking lots of water and taking in the right amount of salt to stay hydrated: which is why an IV drip for when we struggle to drink contains a mix of water and salts called an electrolyte.

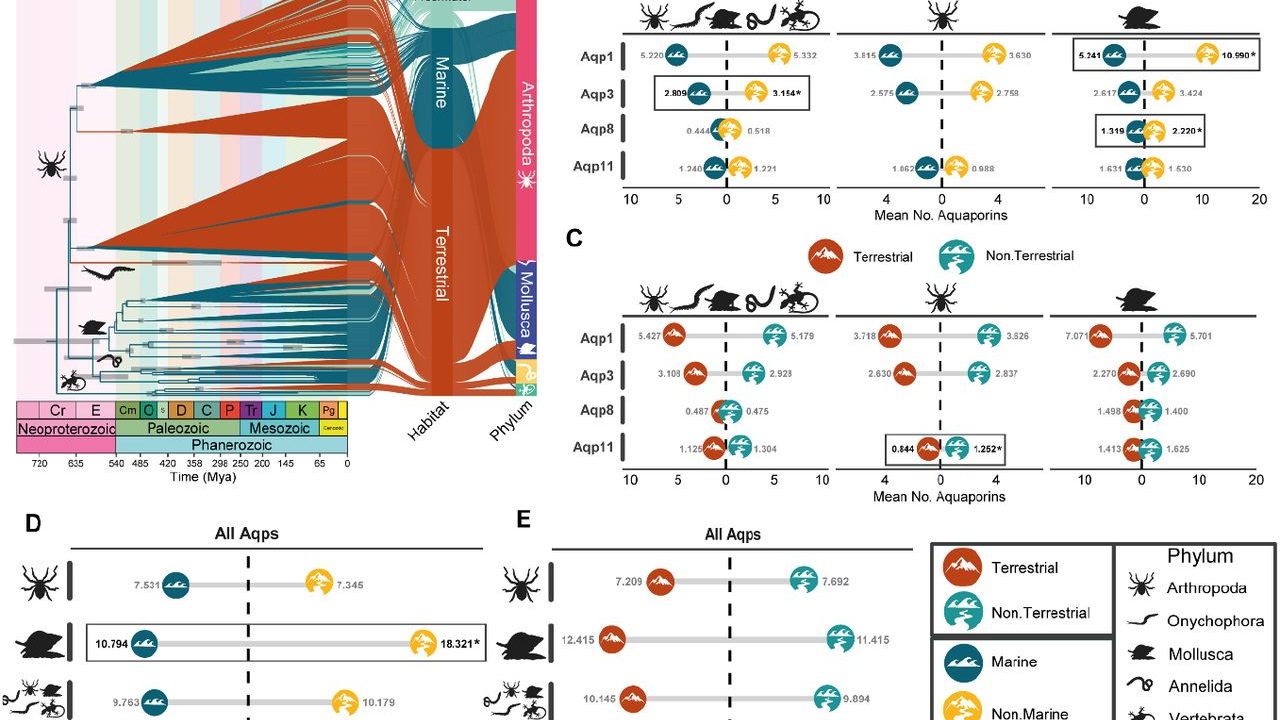

The main figure of the paper: Panel A shows all of the species they found split by terrestrial, marine, brackish or freshwater environments. B, C, D, and E show the different numbers of Aquaporins of each of the families (B and C) and overall (D and E), split by each of the four types: aquaporin 1-like, 3-like, 8-like and 11-like.

Aquaporins are proteins found in bacteria, plants and animals that help control osmoregulation by opening up to let water (and some of the small ions that water carries with it) into the cell. As the work of water regulation is a bit more intensive on land, we might hypothesise that terrestrial animals would have more genes that code for aquaporins, and this was something that Martínez-Redondo et al set out to test. By sampling 458 species from a wide selection of animal groups (vertebrates, velvet worms, molluscs, segmented worms and arthropods), they measured how many aquaporin genes they could find in the genome, and whether that was related to whether they lived on land, or in fresh, brackish or seawater.

The results were a bit more complex than might have been expected at first. When all the animal groups were combined, this theory held true – of the four types of aquaporin, all were more prevalent in non-marine animals than marine ones, but only in one type was this difference statistically significant (more than might be expected by chance). That family – aquaporin 3-like aquaporin – is mostly associated with glycerol permeability which can make animals far more tolerant to drought.

However, when the five groups were split apart, and marine and non-marine species compared again, there wasn’t significantly more aquaporin 3 in any of the five groups! Instead, only gastropods showed significant expansions in any types of aquaporin, and those were aquaporin 1-like and aquaporin 8-like. This might have function in increasing the efficiency of excretion to reduce water loss there, and assist in a process called aestivation, which is like hibernating through summer, when it is hottest. Meanwhile, in arthropods, non-terrestrial species appear to have, on average, a significantly higher number of aquaporins than terrestrial ones, completely bucking the trend!

All this goes to show that the transition to life on land may be a lot more complicated, and more exciting, than we had thought before. These big exploratory studies help shine new light into understudied areas, and show how our preconceived notions of how biology works across life might be far more complex than we’d like. Aquaporins do seem to be related to animal transitions on to land, but there isn’t one true way to make the jump from a watery world to a dry one, with all of those independent movements having their own little signatures across the tree of life.

![]()