After introducing the Artsdatabanken project and telling about our summer collection trips (Trøndelag and Oslo), it is time to present the six invertebrate groups that we are working with. From star ascidians to Christmas-tree worms, this seems to be the adequate time of the year to get to know them.

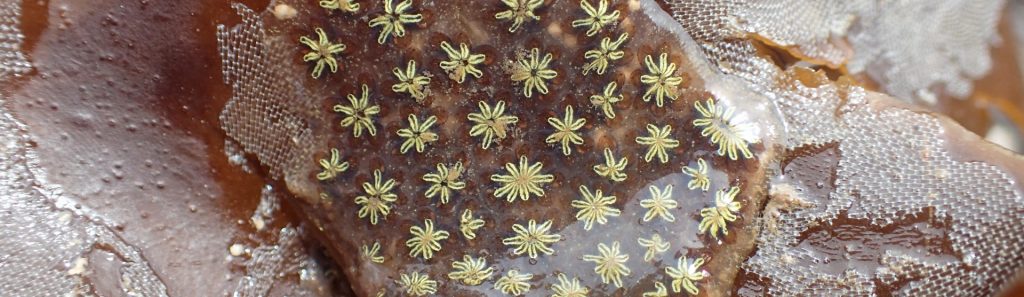

Tunicates belong to the same phylum as humans, but they couldn’t look more different. These animals come in a variety of shapes, colours and sizes and can be solitary or colonial, benthic or pelagic. There are three extant classes, but our project is only dealing with ascidians (sea squirts), the most common and species-rich group. They consist of sessile, barrel-shaped organisms, with two openings (siphons) at the free end of the body. Among the most common sea squirts in Norway is the star ascidian, Botryllus schloserri (Figure 1). This is a colonial species and it takes 3-12 individuals (zooids) to produce one of the star-shaped patterns! Star ascidians usually live on the underside of rocks in tide pools, in rocky reefs or even on kelp fronds.

Caprellidae, also known as ghost or skeleton shrimps, are a family of tiny crustaceans easily recognized by their slender elongated body. Masters of camouflage, they are typically found attached to different kinds of seaweed, using their grasping claws (Figure 2). Most species are predators, remaining motionless for long periods while waiting to ambush their prey, but they can also be grazers, scavengers and filter feeders. Caprellids reproduce sexually and, in some cases, the female kills the male after mating! She then broods the fertilized eggs within her brood pouch and young skeleton shrimps hatch directly as juvenile adults. Caprella mutica, the Japanese skeleton shrimp, is able to have its first offspring less than 2 months after birth, making it an outstanding invasive species.

Nemertea comprises a phylum of slim, long and flattened worms, often with colourful patterns on the body (Figure 3). Their name is associated with the Greek sea nymph Nemertes, daughter of Nereus, the God of Seas. Their most distinctive feature is the presence of a proboscis apparatus, a muscular structure used in capturing food. When inactive, the proboscis lies inside the worms’ body, but it can be everted, jumping inside out to catch prey, making them very efficient predators. Nemerteans also have highly developed muscles that allow them to stretch or contract their bodies several times. The longest animal on the planet, Lineus longuissimus, belongs to this phylum and can reach more than 30m in length!

Entoprocts (Figure 4) are the most elusive of the band, a small phylum containing only about 200 described species. The majority are sessile, colonial filter feeders living attached to algae, rocks, shells, or other marine animals. Their body consists of a goblet-shaped structure with a tentacle crown attached to a long stalk. The solid tentacles in the crown contain cilia that generate water currents that draw food particles towards the animal’s mouth. Even though entoprocts are not rare in shallow waters, they are often mistaken for cnidarian polyps or overlooked due to their small size.

The last two groups are both families within Polychaeta (Annelida), segmented worms with a huge variety of lifestyles. Serpulidae secrete tubes of calcium carbonate, being one of the most important biomineralizers among annelids. They live in the same tube throughout their life, only showing their anterior end, which is covered by feathery tentacles. These hair-like appendages are highly modified structures, which the worms use for feeding and respiration. Another characteristic feature is the presence of an operculum that blocks the entrance of the worm’s tube when they withdraw into it. A remarkable species among serpulids is Spirobranchus giganteus, commonly known as the Christmas-tree worm (Figure 5). Their festive-looking crowns come in various bright colours, making them often prized by underwater photographers and aquarists. Spionidae (Figure 6) are free-living, agile polychaetes. They can be deposit or suspension feeders and use their two grooved palps to locate prey. Some members of this family are capable of boring into calcareous substrate, which has destructive implications for commercially important shellfish.

All these marine invertebrates have significant ecological functions and most groups include cryptic and invasive species. The knowledge about their taxonomy and distribution in Norway is in dire need of improvement, and therefore our project is aiming to contribute to a better understanding of these weird, but beautiful and important little critters.

![]()

2 Comments on “Meet the critters from the Artsdatabanken project”