As we open day 8 on our Advent Calendar, I bring an urgent message.

Maths Can Be Fun, Too!

The Christmas period and the advent calendar gives us a great chance to talk in more general terms about our research. Here at FEZ many of our ongoing research projects have a strong focus on invertebrate biology, and in the calendar this year we have already heard exciting stories of conservation, identification, and sequencing. But to analyse all this new and exciting data, we lean on specialised software and, at the core of it all, lots and lots of maths.

It’s not nearly as cute as the rest of the group’s research, but as the resident FEZ Methodologist, that’s where I come in. When I get asked to define what I research, normally I say I’m interested in Evolution itself as a process: how and why does it work? That means it’s my job to stay at the cutting-edge of all the new ways to analyse all the new data, and to come up with some novel ways to do it myself.

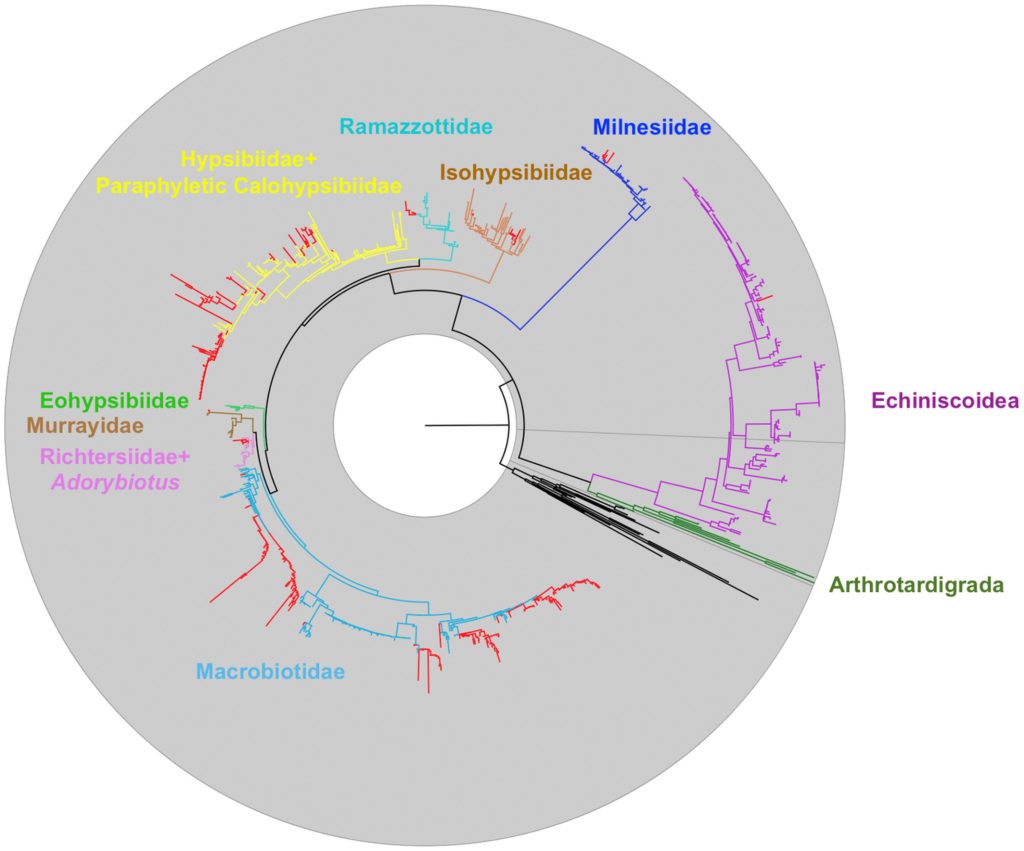

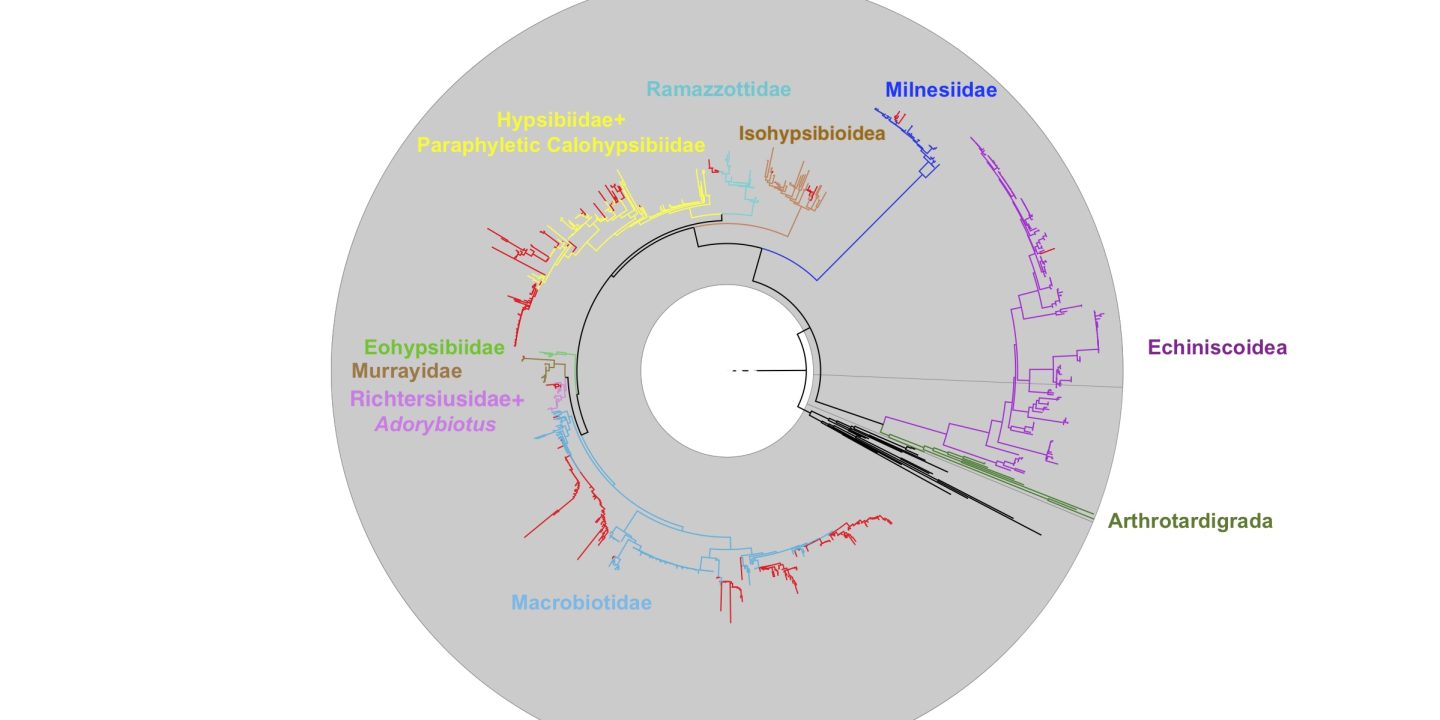

When I say I’m interested in Evolution itself, I also tend to mean phylogeny – the study of how stuff is related to other stuff.

Mutation is a random process – but evolution is far from random. Some of those mutations will be selected for and passed on to the next generation. Some might get passed along because they hang around with the cool, successful genes, and some might get passed along just by luck. It isn’t a perfect system – it’s actually a pretty naff one. An undergraduate lecturer of mine once explained evolution as “like trying to fix a plane in flight – with duct tape”, and I think it’s an apt metaphor.

“Survival of the Fittest” often implies that there is some idea of a “Fittest” thing, a best thing, but that isn’t really true. You can only be good at doing what your species does in the environment you live in at the time you are doing it. A furless polar bear might be really successful in a desert and might work in the arctic a few decades from now, but right now that mutation is going to mean the poor cub doesn’t survive the winter. So we have random change that is constrained by all these tons of factors. Researchers tend to classify them as “abiotic” (like temperature, climate or sea level), “biotic” (the effects of other species around you) and “drift” (the misery of random chance. It doesn’t matter how well suited you are to your island home if that island happens to also be home to a very loud, very angry volcano).

What this creates is a kind of messy picture. Things change, they change back and then they might change again in a totally different direction. The ancestor of mammals, amphibians and reptiles came onto land, then the ancestor of the dolphins and whales returned to the sea. On a few separate, later occasions, different species of dolphins have moved into freshwater, too, just to make sure all the bases were covered.

These convoluted paths exist in DNA sequences, too! That means we can’t just count changes that we see and end up with a nice understanding of how all these animals are related to each other. If we want to puzzle out the threads of evolution – we must think like evolution. And since evolution operates on a mix of randomness, luck and selection – that means we need mathematical models: a mix of algebra, calculus and statistics.

And sometimes, these models break down. I went into a lot of detail about all the assumptions we make in our models earlier this year, and when they can leave us all looking a bit silly.

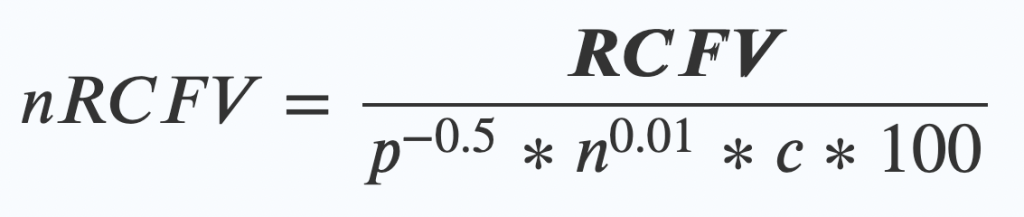

This year, FEZ has had a few articles about tools that work out when, how and why those models break down – it’s one of the things I’m most interested about (maybe even more than making better models, which is a fault of mine, I’ll admit!). nRCFV is a new tool we’ve made that helps researchers work out how messy those evolutionary histories are. Scoutknife is a new tool that tries to get around those messy histories by throwing as much data as possible at the problem. I’ve already written blogs about those, and about our review, which is all about how models break down, so I won’t dwell on that too much!

It’s a very dark and cold December evening as I write this in Oslo, which means I wanted to highlight some other lights in the dark: we’re not alone in these efforts. There are tons of researchers, all across the planet, all interested in these kinds of questions. In March, we hosted a symposium in Oslo where we invited researchers from the United States and Europe to talk about recent progress in these ideas, and we had hours of exciting discussions about where the field might be going, and what problems we might encounter next.

In December last year, Julia Haag and colleagues released Pythia, which takes a unique approach to understanding phylogenetics: it uses new machine-learning methods to work out how difficult your data is to analyse before you even analyse it. This opens up so many possibilities for evaluation, and seems like a thoroughly exciting and novel way to understand the data we work with.

In sunny July for us in Oslo – and the chilliest for his group in Auckland – Drummond and colleagues released LinguaPhylo. This is a new way of coding the phylogenetic models I mentioned in part 2 that makes them a lot easier to read. It’s a significant improvement for creating a unified understanding of how these things work. This allows us to make clearer and more complicated models more easily, and might open up an entirely new way of understanding how they work.

Understanding evolution didn’t stop or start with Charles Darwin writing the Origin of Species in Shrewsbury in the 1850s. It’s a process that has been ongoing since we started to understand that children often look like their parents, that has been revolutionised by our discovery of DNA, and that has been supercharged by the increasing computational power we have access to. But at the core of it all, from the Stone Age to the Space Age, are excited, curious people who are thrilled to learn what comes next – and I’m on the edge of my seat to see what the next year brings.

![]()

2 Comments on “Day 8: Working in Phylogenetic Methods”