By Pia Merete Eriksen and Rita M. Austin

I think most of us conceptualize a seal as a comical or cute animal, darting through open waters – I don’t think many of us envisage blood-red balloons and bulging sacs, specialized for a ritual of dominance and mating. Enter, Cystophora cristata, the hooded seal.

Where females and pups match the images in our head of a blubbery silver-grey seal, male hooded seals have inflatable lumpy protrusions on their heads and noses (the hoods; Figure 1.). Additionally unique to C. cristata males, is their ability to inflate their nasal septum, pushing it out of one nostril like a large balloon (Figure 2). The hood and nasal bladder are used to attract females and to show aggression towards competing males during the March mating season.

Photo – Sylvian Cordier

Photo – Sylvian Cordier

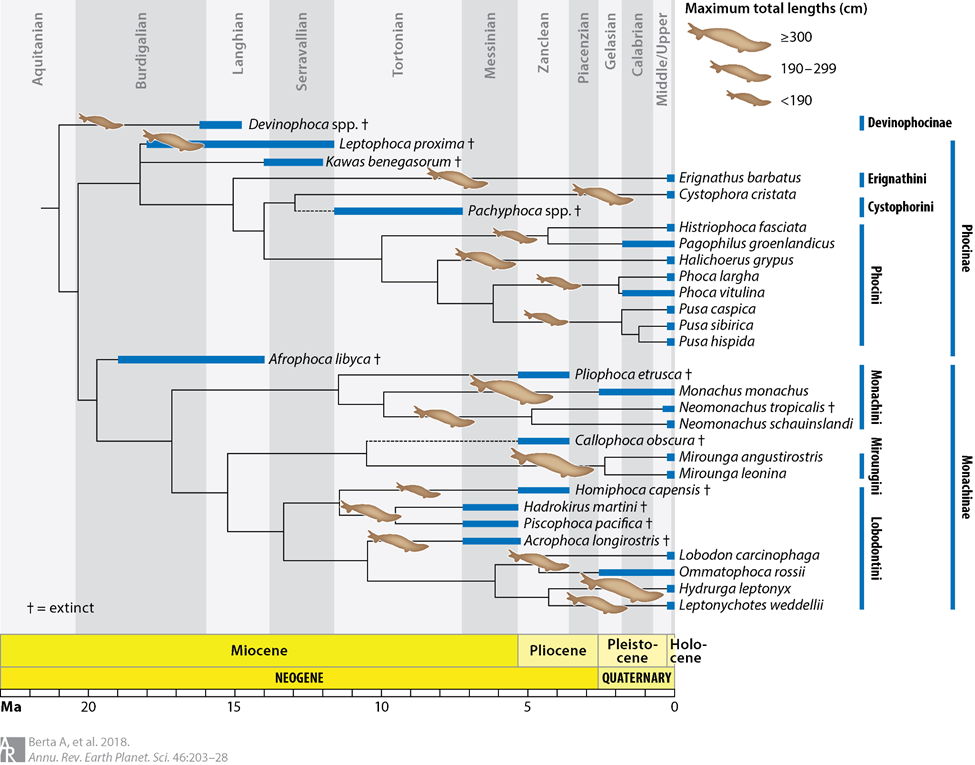

Within the Pinnipedia clade, which includes other familiar faces such as walruses, sea lions and leopard seals, hooded seals stand separately from their closest relatives in Phocinae (e.g., ribbon seals, bearded seals) (Figure 3). Their closest relative is likely the extinct Pachyphoca spp. (Berta et al. 2018). On a genomic level, however, not much is known about the hooded seal. Notably, cytochrome B and the D loop are well documented, but the full genome is yet to be sequenced, which may reveal interesting insights in their population structure and evolutionary history.

Image taken from Berta et al. 2018, modified from Fulton & Strobeck (2010) and Amson & de Muizon (2014)

Hooded seals inhabit arctic atlantic waters, with coastal territories in eastern Canada, Greenland, Iceland and Svalbard. Numbers have been decreasing over the last 60 years, going from an estimated 500,000 to 70,000. This is suspected to be for a number of reasons, including baby “blue-back” seals (Figure 4) hunted for their coats, fishing accidents, and the impact of climate change. Relying on pack ice during short breeding seasons – ice that doesn’t connect to the mainland and drifts on ocean currents – hooded seals have less and less pack ice breeding localities due to increasing global temperatures, endangering their survival.

Photo – Northeast Fisheries Science Center

Another unique trait of the hooded seals are their short lactation periods of only 3 to 5 days – the shortest known in any mammal! With incredibly fat dense milk, hooded seals gain a dramatic amount of neonatal weight during this period, at a rate 2.5 to 6 times faster than other phocids, gaining an average of 7.1kg per day (Bowen et al., 1985). This adaptation proves useful given the tumultuous pack ice used for birthing.

Take a look at this video from Nat Geo WILD to see males fight for dominance in a dramatic balloon-blowing competition!

References:

Bowen, W.D., Oftedal, O.T., Boness, D.J., 1985. Birth to weaning in 4 days: remarkable growth in the hooded seal, Cystophora cristata. Canadian Journal of Zoology 63, 2841–2846.

Berta, A., Churchill, M., Boessenecker, R.W., 2018. The origin and evolutionary biology of pinnipeds: seals, sea lions, and walruses. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 46, 203–228.

Banner photo credit – Sylvian Cordier

![]()