Living in and on our bodies are trillions of microbial cells belonging to thousands of bacterial species – our microbiome.

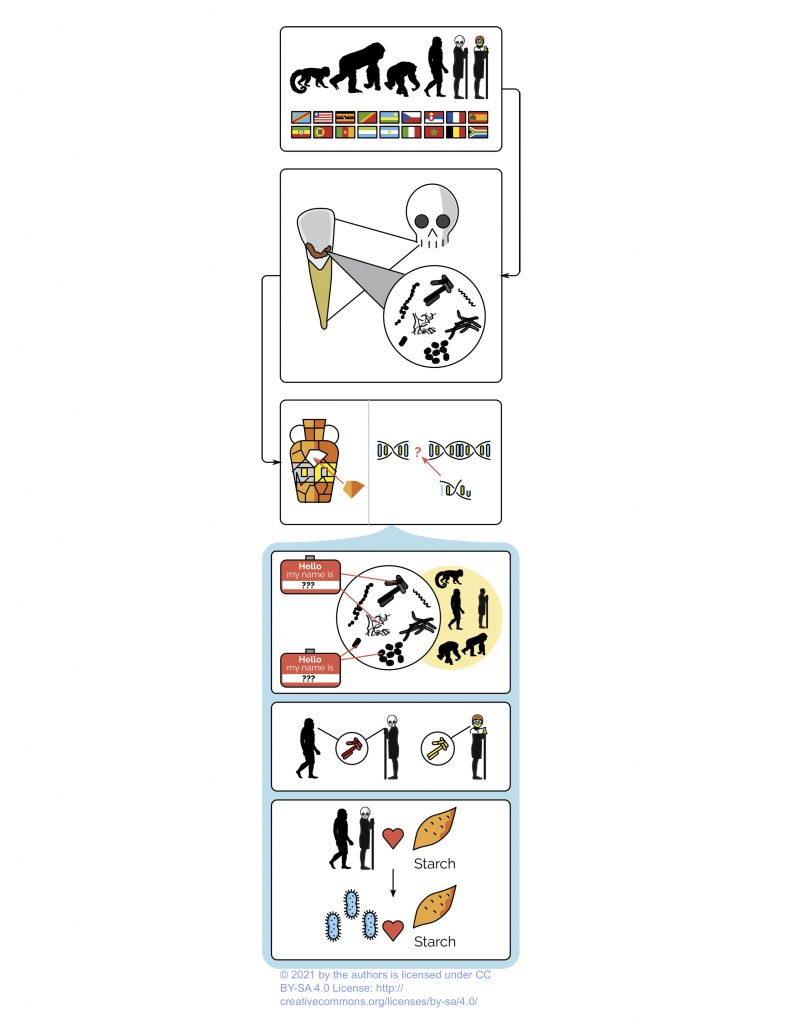

These microbes play key roles in human health, but little is known about their evolution. Here we investigated the evolutionary history of the hominid oral microbiome by analyzing the fossilized dental plaque of humans and Neanderthals spanning the past 100 thousand years, compared to those of chimpanzees, gorillas, and howler monkeys (Figure 1).

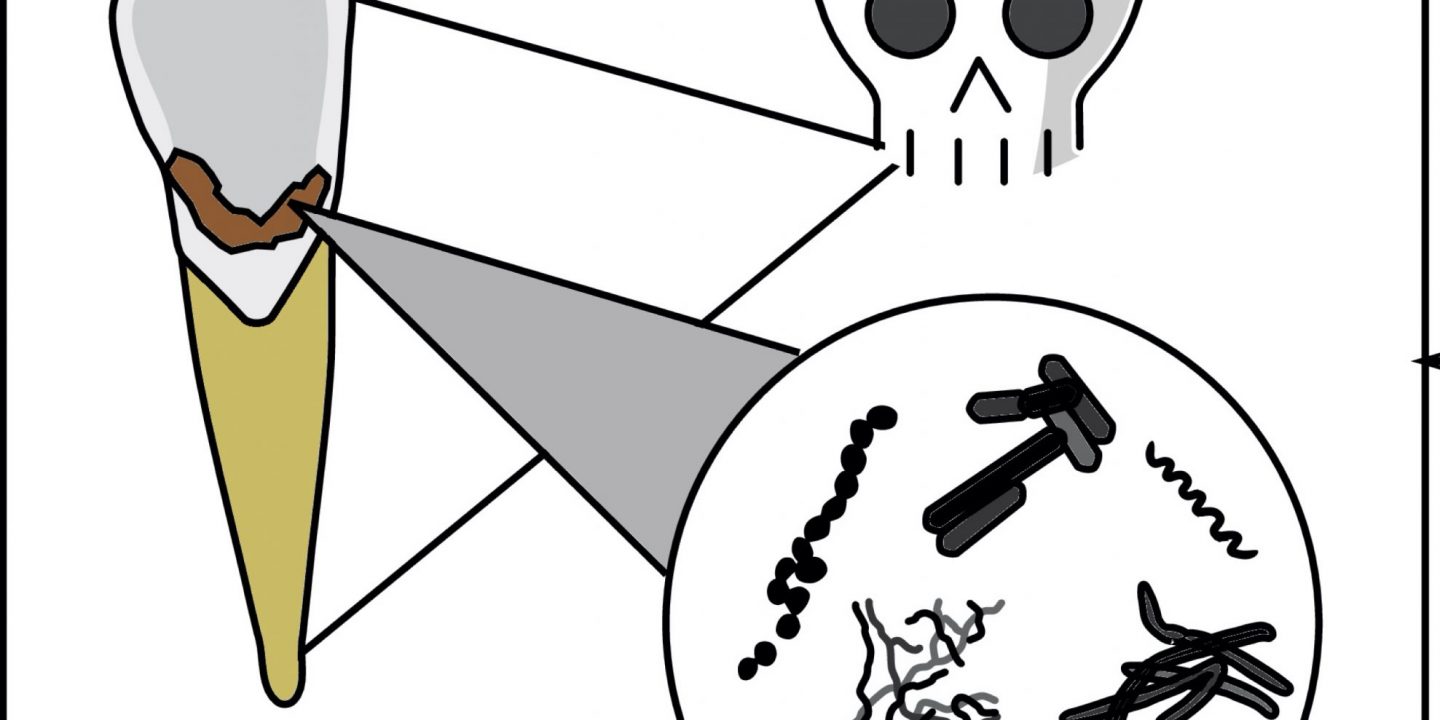

Working with DNA this old is highly challenging, and like archaeologists reconstructing broken pots, archaeogeneticists also have to painstakingly piece together the broken fragments of ancient genomes in order to reconstruct a complete picture of the past. To achieve this, we developed new tools and analyses to genetically analyze billions of DNA fragments in order to identify the long-dead bacteria preserved in the archaeological record.

From the fossilized dental plaque, we identified ten groups of bacteria that have been members of our oral microbiome for over 40 million years and that are also still shared with our closest primate relatives. These bacteria have important and beneficial functions in our mouths and may help promote healthy gums and teeth. Surprisingly, however, many of these bacteria are poorly studied and some don’t even have names! Although we share many oral bacteria with other primates, our oral microbiome is most similar to Neanderthals. In fact, the oral bacteria of modern humans and Neanderthals are nearly indistinguishable. However, a few small differences do exist, and we found that ancient humans living in Ice Age Europe shared some bacterial strains with Neanderthals, although these strains are no longer present in humans today. Most surprisingly, we found that one group of bacteria present in both modern humans and Neanderthals is specially adpated to consume starch. This suggests that starchy foods became important in the human diet long before the introduction of farming, and in fact even before the evolution of modern humans. Starchy foods, such as roots, tubers, and seeds, are rich sources of energy, and some have argued that our ancestors’ transition to eating starchy foods may have been what enabled humans to grow the large brains that characterize our species. Reconstructing what was on the menu for our most ancient ancestors is a difficult challenge, but our oral bacteria may hold important clues for understanding the early dietary shifts that have made us uniquely human.

Our oral microbiome has coevolved with us over millions of years, but despite major scientific advancements, we still know very little about it. The humble plaques that cover our teeth and that we carefully brush away every day, hold surprising clues about our evolution and valuable information about our everyday health.

For the full scientific article, please see:

Fellows Yates et al. (2021) ‘The evolution and changing ecology of the African hominid oral microbiome’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 e2021655118. DOI https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2021655118

Funding

University of Ferrara; Ministry of Culture-Western Veneto Archaeological Superintendence SABAP and the Zovencedo Municipality; H. Obermaier Society; R.A.A.S.M.; Saf; The Calleva Foundation; European Research Council; the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada; Czech National Institutional Support; Ministry of Culture and Information and the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia; Junta de Castilla y León; National Research Foundation of South Africa; Swedish Research Council Formas; University of South Florida; U.S. National Institutes of Health; University of Oklahoma; Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft; Werner Siemens-Stiftung; U.S. National Science Foundation; Max Planck Society.

Image Credits

openemoji.org – Skull: Mariella Steeb; Amphora: Hend Hourani; DNA: Tonia Reinhardt; Heart: Laura Humpfer; Scientist: Benedikt Groß; Tuber: Miriam Vollmeier; Microbe: Ricarda Krejci; Flags:Ferdinand Sorg; Carlin MacKenzie; Daniela Ivandikov. CC icons: Carlin MacKenzie (all CC BY-SA 4.0).

phylopic.org – Chimpanzee: T. Michael Keesey (vectorization) and Tony Hisgett (photography) (CC-A 3.0); Tannerella, Fusobacterium, Actinomyces, Neisseria: Matt Crook (CC-A-SA 3.0); Treponema: Gareth Monger (CC-A 3.0).

*Original press release content, images, and quotes created and licensed by Christina Warinner, Irina Velsko, and James Fellows Yates (© 2021 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/). Reproduced here for promotion and co-author blog.

![]()